Many of you will have read this story before. If you haven't, and you haven't read much Raymond Carver, know that this one is considered by him and others to be a turning point in his famous career, one in which three people find some small, quiet peace in communion.

For purposes of observing craft through the lens of this piece, consider what Baxter says about characterization: "Plot often develops out of the tensions between characters, and in order to get that tension, a writer sometimes has to be a bit of a matchmaker, creating characters who counterpoint one another..." (88). He suggests that in a crafted combination, characters have "a crucial response to each other."

|

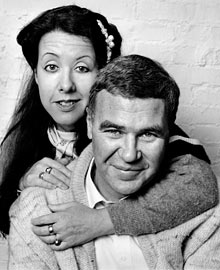

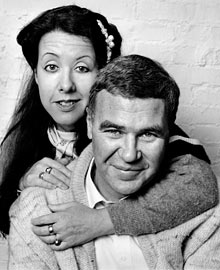

| Raymond Carver with his wife, the poet Tess Gallagher, photographed in 1984, in Syracuse, New York. Photograph: Bob Adelman/Corbis |

Consider, too, Baxter's reclamation of "rhyming" for prose. This is similar to my analogy of a rollagraph or stamping wheel. I love his idea of "beautiful action" (113), actions that "feel aesthetically correct and just--actions or dramatic images that cause the hair on the back of our necks to stand up, as if we were reading a poem," and he concludes that this kind of sublime experience "has to do with dramatic repetition, or echo effects." I will suggest, although it is for you to elaborate upon, that "Cathedral" is magnificent because of its (Baxter-redefined) rhyme.

I think I'll respond creatively with this one by writing a little story like "Cathedral" that does what Baxter says. I'll create two characters that don't work well together, and put them in a setting together, and see if a plot is able to emerge from the tension.

ReplyDeleteMac and Lou were sitting at a round table after midnight. They were in the library of their university preparing a group presentation for their sociology class the next day. Lou was on his laptop trying to make their power point look nice by adding pictures and colors.

“C’mon it’s fine. Do you really have to do this?” Mac mumbled his arm sliding across the table as his head was suddenly too heavy to hold it.

“I don’t have to do it, you can. It was originally your job.”

“Yeah, and I didn’t because it was pointless.”

“Well then now you’ll have to wait for me to do it,” Said Lou

With a big grunt, Mac buried his face in his arms.

“Why don’t you practice what you are going to say tomorrow?”

“Just tell me what slides to read when we’re up there, and I’ll read them. Let me just go to sleep now.”

“It’s not enough just to read what’s on the slide. You need to have something to say about each point. And look,” Lou grabbed a few index cards that were sitting on the table in front of Mac. “Here are those index cards that told you to memorize.”

Mac rolled his eyes

“If you had memorized them, you would know exactly what to say on each slide.”

“I’ll read from them when we’re up there presenting.”

“No. I’m not letting you mess up our presentation. I don’t know why professor Winegardner put us together, but I’m not letting you mess up my GPA.”

“Dude, we’re going to do fine. I’m not gonna ruin your precious GPA”

“Fine isn’t good enough. I’ve never gotten less than an A since middle school.”

“You’ve never gotten less than an A on anything?”

“Nothing.”

“Wow you’re crazy bro.”

Lou frowned. He looked at the power point carefully and continued adding things. “Alright. I still have some more pictures I want to add to this, but you can go if you promise you’ll memorize those index cards by tomorrow.”

“Sure I will,” Mac yawned and stretched his palms to the air. “See ya tomorrow.” Mac got up and left the library.

Lou sat still at the table for a minute. Maybe I should have made him stay here to make sure he memorized those cards. Not completely trusting Mac, Lou returned to the power point and tried to make it look extra nice. Perhaps it could gain back some of the points Mac was bound to lose him.

I, too, have elected to do a creative response. There's a lot of things in "Cathedral" I could have tried to mimic, but I chose to focus on the voice of the narrator. He's so jovial and conversational about telling his story. He uses exclamation points. Despite his cynicism and prejudice, there's a certain wonder--a "Can you believe this?" quality--to his words, and that's what I've tried to capture in this exercise.

ReplyDeleteA friend of mine, he bartends at MacLaren’s on weeknights, told me this story the other day. Boy, I thought this was rich. I sat down at the bar on Monday night and ordered a scotch and soda. While Reggie, that’s his name, was fixing my drink, he told me this story. I don’t remember what he said word for word exactly, but I’ll tell you anyway. First, he tells me, this all happened last Saturday night. I wasn’t there because Saturdays and Sundays I spend at home with my wife, Elisa. I come to MacLaren’s on weeknights for a drink between the office and my house. Some days I duck out of the office a little early. Anyway, Reggie is telling me all sorts of background stuff about how he was covering another bartender’s shift. That part was boring. I’ll skip it. You’re lucky you’re hearing this story from me and not him.

The good part comes when Reggie tells me about eleven o’clock when this woman walks in carrying, get this, an infant. Can you believe that? The woman, Reggie says, looked like she could have been pretty if she did her hair and lost a few pounds. The kid, according to Reggie, couldn’t have been older than a year old. This crazy lady brought a goddamned baby into MacLaren’s Pub. Some people, I just don’t get them.

Of course she’s getting all sorts of looks as soon as she comes in. She doesn’t mind them at all, just carries her kid over to the corner and stands near the jukebox. Reggie wants to go over there and ask her what her deal is. Tell her that what she’s doing isn’t appropriate or whatever. But there’s a big Saturday night crowd. So he’s stuck behind the bar, swamped with drink orders. For twenty minutes he stares at her. She rocks her kid back and forth.

It gets weirder. The mystery woman starts to lower her blouse. For a second Reggie thinks she’s undressing. By now most people have gone back to their drinks and friends and conversation. They’ve forgotten about her. But Reggie is still staring, wondering what the fuck is with her, and that’s when she starts nursing her kid. “No fucking way,” I said to Reggie, but he swears it’s true. He swears on his life, on his mother’s grave, to God, the works. Some woman breastfed a baby in the corner of MacLaren’s by the jukebox.

So of course by now Reggie had to go over and say something. He leaves the bar and walks over to her. She turns away from him slightly but doesn’t stop what she’s doing. Reggie says something like, “Ma’am, I don’t really think this is the place for a child.” She doesn’t say anything back. So Reggie says, “You’re not allowed to do that here, not in public.” She ignores him, doesn’t even look at him, just keeps her eyes on her kid’s head. “Ma’am,” Reggie booms, “I’m going to have to ask you to leave.”

This part really gets me. As if this woman wasn’t out of her mind enough, get a load of what she does next. She turns her head, looks Reggie dead in the eye, and shushes him. The balls on this lady! Am I right? Well you can imagine that Reggie was pissed by this point. But he looks around and people are staring again. Some people want to know what the fuss is about. Others just want their drinks. He sees one guy reaching behind the bar for something. Reggie, poor guy, is helpless.

(It goes on, but I've hit the word limit.)

I really enjoyed the Cathedral because to me it felt very different from the other pieces and it had one of the things that interest me (not in a creepy or weird way), which is blindness. I also found it interesting to see how people react to blind people and how the person deals with not being able to see and Raymond Carver took that and made it very fascinating to see the interaction between the narrator and a blind man.

ReplyDeleteAt first I despised the narrator for being very judgmental about a person he never met before. Yet as the story progressed, I realized that the narrator and me were actually similar as his situation is very relatable and I begun to sympathize with him more. By the time the ending came I, like the narrator felt like I was being changed as well. I felt like I was learning a valuable lesson on how to treat people and to not be judgmental that the ending was one of my favorite parts because I feel like I too accomplished something. I guess this is because the narrator had this conversational tone that made me feel like I was there with him observing everything. It made me realize as a human being some of the faults that I have towards people and sort of taught me a way to get past it.

But the narrator and the techniques of creating such a unique blind man is just another reason why I really admired Raymond Carver. I read two stories by him last semester and I’m still impressed with the way he crafts details and creates these realistic characters. He also writes about events that people really take for granted or don’t want to read about such as a woman losing her child in “The Bath” or blindness in “Cathedrals”. This inspires me to try and write stories that don’t appear in many popular fiction novels but pertains to real life. These events or people that Carver writes adds to the realistic atmosphere even if it is darker than people see it as.

As I began to like the narrator more and more, I began to dislike the narrator’s wife more. I don’t know if it is because I found her to be extremely annoying or that she was just in the way. But I do think she served a good purpose for the story. She pushed the narrator to change by sleeping. Yet I don’t know if she was supposed to change at all. In fact she doesn’t have the ability to change at all and refuses to because she is afraid to.

I think in terms of Baxter’s counterpointed characterization, this story is probably a very good example of what happens when you put two very different people together and that is also what made the story very compelling. It gave lots of evidence to what Baxter was talking about and I helped make the change happen quicker. The conflict in the story was just the narrator trying to deal with his judgmental view of blindness and wasn’t very dramatic or out there that might be necessary to carry a story through. It was just about three people sitting in a living room together all of them very different from one another.

To my surprise, I had read "Cathedral" before, presumably in Intro to Fiction. That said, I really like the placement of the three stories. There's a real element of repetition in these stories - all of them have characters with verbal tics but there are also characters who repeat words or phrases that often don't make sense. It made the stories a bit difficult to get through, but it was also clearly deliberate, and so I was able to set aside my annoyance at the element of repetition.

ReplyDeleteI think there's an interesting progression from one story to the next in how heavily stylistic they are. "Are These Actual Miles?" had particular moments that threw me, that were presumably "Carveresque," but "What We Talk About When We Talk About Love" had a more constant current of repetition and verbal tics as well as interesting formatting - the breaks between sections gave me pause. "Cathedral" has the strongest voice, obviously, and I can understand why it would be a turning point in Carver's career.

All three stories feature some distinct themes - bankruptcy, alcohol, failing or failed marriages as well as second marriages. And yet the characters and their situations were entirely different. I think that's the remarkable thing about Carver's writing for me. He uses so few pages to talk about similar themes, and yet I don't see major similarities in characters or forget which story I'm focusing on. They're distinct, even when the voice isn't as strong as that in "Cathedral".

In the introduction, Chaon says that Carver’s moments of awe “are not fake, his humor is not coy or condescending. In short, he’s not a phony,” and also that “he was able to give significance to unheroic lives.” These sentiments materialize in “Cathedral,” where we see a down-to-earth, meat-and-potatoes narrator reach a level of consciousness that is everything but.

ReplyDeleteCarver sturdily places the narrator in the role of “average middle class” character by having him speak in short, staccato sentences—sometimes as vague and un-literary as “So okay.” The narrator is speaking to us, not trying to craft well-structured sentences or embellish anything. He even directly denounces poetry, admitting that “Maybe I just don’t understand poetry. I admit it’s not the first thing I reach for.”

Once the narrator is in that simple, yet remarkably endearing personality, Carver can get away with a lot of “dangerous” things. He dips his toes into cliché—no, actually, he completely dives into them—not only is there a quasi-prophetic blind man leading the narrator through the moral of the story, but the blind man’s wife died of cancer of all things. On top of that, Carver avoids finishing Robert’s thought, “From all you’ve said about him, I can only conclude—”. I won’t call it a cop out, because this is Raymond Carver we’re talking about, but c’mon, we have to admit that it’s pretty close. We let it slide, though, because the narrator he’s set up is one that is realistic and middle-class enough to let it slide. It’s brilliant, really, to use the narrator’s shortcomings as a way to dodge potential accusations of simplicity or cliché.

I've read Cathedral before, and it always leaves me with a bittersweet feeling.

ReplyDeleteI see things, not how anyone else sees them, but in a unique way, my mind's eye. As I get older, I have been losing touch with my idea of what things look like. It's been 15 years since the accident which rendered me blind, and what bothers me most, is my inability to remember, or even know at this point; what I look like. I feel like I have no identity.

I pick ups something and fiddle with it in my hands. It is cold and has some weight, must be metal. I turn it over and feel it's oval shape. There's a bump in one side, its a hinge. I open the locket Jenna gave me while I was recovering in the hospital. I hold this dear to me. I run my thumb over the ridges holding the picture inside the locket. I think there's a picture, but I cannot be sure. It doesn't matter, I'll never see the photo anyway.

I just gotta shake it off, I can't let it get me down at this point. I walk the memorized path from by bedroom to the front door of my house. I walk outside ad warmth surrounds my body. Seems like a good day for a walk. I step out onto the sidewalk and begin a brisk walk. I continue about a block. Rumbling, revving, I stop, concentrate. There's a car coming don the street horizontally in front of me. I listen for the sounds to pass, and I continue on my way. I hear a faint clomp, clomp. I woman in heels is approaching. Id pace left slightly to allow her to easily pass while still on the sidewalk.

Carver’s characters are very actively present in their own world. Even this narrator, who is sort of nondescript and indifferent towards a lot of things, has a strong voice with a very conversational tone. At first it sort of sounded like a student’s writing at first. Maybe I’ve just read too many stories about apathetic characters that are uninfluenced and unmotivated, which often times makes the character lack depth and personality. But in Cathedrals, that detached attitude becomes a surprisingly solid structure to bass a character from. Probably because with the arrival of the blind man, the narrator feels himself being challenged. He speaks in short choppy sentences. He doesn’t necessarily adhere to the rules of grammar and punctuation. And all of this is perfectly in line with his character. As Alex has mentioned the example of this that most stuck out in my mind is the fact that the narrator doesn’t like poetry. He just doesn’t “understand” it.

ReplyDeleteBut with Robert in the house he finds himself taking note of things he wouldn’t have cared about before. And even though sits by and lets his wife and guest dominate the conversation throughout the evening never gives us the sense that he loses himself. Rather he depict how he tries to maintain a presence in the scene, although his attempts don’t always prove to be successful.

I think that if this story had ended in a different way I probably wouldn’t have liked it very much. I like that you start to see the character change without coming to some sort of grand epiphany which often happens in longer works of fiction. His shift in attitude and opinion is very subdued, almost to the point that even he doesn’t quite seem to quite recognize it himself. I think that notion works much better for short stories.

This is my third time reading Cathedral, but I read it with a different eye than I had previously. Catherine and I spoke about counterpointed characters in my conference yesterday in relation to my short story. I went back and reread the Baxter chapter about it and was able to relate it to Carver. Baxter says, “With counterpointed characterization, certain kinds of people are pushed together, people who bring out a crucial response to each other” (88). Two characters do not have to be complete opposites for tension to arise. Baxter says that counterpointing substitutes for conflict, such as the relationship between the narrator and the blind man. The conflict is created by putting the two of them together and seeing how they react. The contrast is sometimes straightforward and simple (like in fairytales or parables), but more often than not, it’s not black and white.

ReplyDeleteThe mention of Carver’s use of fairy-tale archetypes in the introduction caught my eye. I’d never thought about it until today, pairing it with Baxter’s idea of counterpointed characterization. Fairy-tale characters have the potential to seem hokey and cliché, but Carver writes the blind man in such a detailed way that he seems very real to me. Smoking with the narrator, drinking Scotch, and hearing the difference between color and black and white TVs, all these specifics give him a personality deeper than the wise old blind man stereotype.

The narrator feels so real to me, both through his dialogue and inner thoughts. He is insecure about this blind man coming to his house to visit his wife, who used to read to him. In the first two pages of the story he thinks things like, “His being blind bothered me. My idea of blindness came from the movies” and “Her officer—why should he have a name? he was her childhood sweetheart, and what more does he want?” His tone is blunt and honest, and it characterizes him immediately to readers as a defensive and insecure man.

Like what seems like everyone, I’ve elected to do a creative response. While reading the piece I asked myself how it would be different if the narrator were a woman, so I’ve decided to write the piece in a wife’s POV:

ReplyDeleteI’m not going to say that it makes me comfortable that my wife is bringing a blind man home. A blind man whose wife has died, who is looking for comfort within another person, within my wife. He’s arranged to come over after he visits his in-laws, by train of course, blind people cannot drive. After a five-hour journey he’d meet my wife, Sandra, at the station and she’d bring him here. I’d drive for her, so she could speak to him in the back seat so things would be more at ease and so when we all got home things wouldn’t be awkward. She had worked with him a few years ago, reading things to him and such. Then when we moved they started mailing these tapes back and forth. I wasn’t too excited about him coming to visit; I didn’t know how to act around a blind person, if there were another set of manners to adhere to. Would he notice if he didn’t look at him while I talk or cross my legs on the couch?

That summer in Chicago Sandra needed a job, money around the house was tight and I couldn’t spare any for things that either of us wanted. She wanted to marry some guy at the end of the summer, but he was in officers’ training school and she was in love with him. She was reading the paper and saw: HELP WANTED—Reading to a Blind Man, she called and was given the job immediately. Over that summer she broke up with this ‘man of her dreams’ because she was a jerk about her working, let alone working with another man. She stayed employed till the end of the summer, reading stuff to him, case studies, reports and the like. They’d become good friends, Sandra and our guest. On the last day in the office he’d asked if he could touch her face and she agreed. He’d touched his fingers to every crevice, her eyes, her nose, her neck. She never forgot it, it inspired her barren fingers to write poetry. She got a poem or two every year from then on, usually after something important happened to her.

When I first read Cathedral, I didn’t know what to make of the narrator. He seems so indifferent towards life in general, just sort of drifting his way through his mundane world. I am finally able to see some bit of spark from him when he is sharing his thoughts on blind people and how he doesn’t want this blind man to be in his house.

ReplyDeleteAs shown through his telling of his wife’s backstory but her officer, the audience knows that he is uncomfortable with the idea of a man who knew his wife before he did, in a way that he still does not know her. Robert, or as the narrator continuously thinks of him, the blind man, is one of those men who was a past presence in his wife’s previous existence. The narrator seems to be holding on to the fact that he is blind as a sort of fault or vice that will counter balance the friendship that he is not a part of.

Despite himself, the narrator does form a type of friendship with Robert, so slowly and subtly, that he does not even realize it until the last moments on the page. Now, the wife is on the outside looking in, and Robert has somehow managed to make the husband see past his own stubborn prejudice. And all it took was sharing some dope and a drawing lesson.